Bowel Disease (Short bowel syndrome)

Published: 18 Jun 2025

ICD9: 579.3 ICD10: K90.82 ICD11: DD7Z

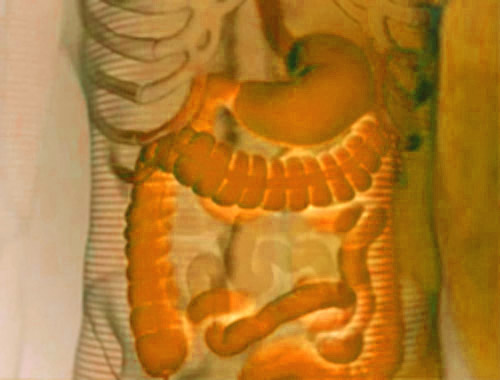

Short bowel syndrome (SBS), also known as short gut syndrome, is a condition that occurs when a person's small intestine is significantly shortened or damaged, resulting in the inability to absorb enough nutrients from food.

In simpler terms, their gut isn't long enough or healthy enough to do its job properly.

Here's a breakdown of the key aspects:

What it is:

![]() Reduced Intestinal Length or Function: The primary issue is insufficient small intestine length or compromised function. A healthy small intestine is usually around 20 feet long in adults. People with SBS might have significantly less, sometimes as little as a few feet. Even if the length is adequate, the intestine might be damaged by disease or inflammation, preventing proper absorption.

Reduced Intestinal Length or Function: The primary issue is insufficient small intestine length or compromised function. A healthy small intestine is usually around 20 feet long in adults. People with SBS might have significantly less, sometimes as little as a few feet. Even if the length is adequate, the intestine might be damaged by disease or inflammation, preventing proper absorption.

![]() Malabsorption: The shortened or damaged intestine can't absorb sufficient amounts of essential nutrients, including:

Malabsorption: The shortened or damaged intestine can't absorb sufficient amounts of essential nutrients, including:![]()

![]() Macronutrients: Carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

Macronutrients: Carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.![]()

![]() Micronutrients: Vitamins and minerals.

Micronutrients: Vitamins and minerals.![]()

![]() Fluids and Electrolytes: Water, sodium, potassium, etc. This is a major concern in SBS, leading to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.

Fluids and Electrolytes: Water, sodium, potassium, etc. This is a major concern in SBS, leading to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.

![]() Consequences: This malabsorption leads to a variety of problems, including:

Consequences: This malabsorption leads to a variety of problems, including:![]()

![]() Malnutrition: Deficiencies in essential nutrients.

Malnutrition: Deficiencies in essential nutrients.![]()

![]() Diarrhea: Frequent, watery stools due to unabsorbed fluids and electrolytes. This is a hallmark symptom.

Diarrhea: Frequent, watery stools due to unabsorbed fluids and electrolytes. This is a hallmark symptom.![]()

![]() Weight Loss: Inability to maintain a healthy weight.

Weight Loss: Inability to maintain a healthy weight.![]()

![]() Dehydration: Loss of fluids through diarrhea.

Dehydration: Loss of fluids through diarrhea.![]()

![]() Electrolyte Imbalances: Can cause serious health problems, including heart rhythm abnormalities.

Electrolyte Imbalances: Can cause serious health problems, including heart rhythm abnormalities.![]()

![]() Fatigue: Due to lack of energy from malabsorption.

Fatigue: Due to lack of energy from malabsorption.![]()

![]() Vitamin Deficiencies: Leading to various health problems depending on the specific vitamin deficiency.

Vitamin Deficiencies: Leading to various health problems depending on the specific vitamin deficiency.![]()

![]() Bone Disease: Malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D can lead to osteoporosis.

Bone Disease: Malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D can lead to osteoporosis.![]()

![]() Kidney Stones: Changes in bowel function can increase the risk.

Kidney Stones: Changes in bowel function can increase the risk.![]()

![]() Liver Problems: In some cases, especially with long-term parenteral nutrition (see below).

Liver Problems: In some cases, especially with long-term parenteral nutrition (see below).

Causes:

SBS can result from various factors, including:

![]() Surgical Resection: This is the most common cause. Surgery to remove a portion of the small intestine might be necessary to treat conditions such as:

Surgical Resection: This is the most common cause. Surgery to remove a portion of the small intestine might be necessary to treat conditions such as:![]()

![]() Crohn's Disease: Chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

Crohn's Disease: Chronic inflammatory bowel disease.![]()

![]() Mesenteric Ischemia: Blockage of blood flow to the small intestine, leading to tissue damage and potential need for removal.

Mesenteric Ischemia: Blockage of blood flow to the small intestine, leading to tissue damage and potential need for removal.![]()

![]() Volvulus: Twisting of the intestine, cutting off blood supply.

Volvulus: Twisting of the intestine, cutting off blood supply.![]()

![]() Tumors: Cancerous growths.

Tumors: Cancerous growths.![]()

![]() Trauma: Injury to the abdomen.

Trauma: Injury to the abdomen.

![]() Congenital Conditions: Babies can be born with a shortened small intestine (e.g., intestinal atresia).

Congenital Conditions: Babies can be born with a shortened small intestine (e.g., intestinal atresia).

![]() Diseases Affecting Intestinal Function: While less common causes, certain diseases can damage the intestinal lining and impair absorption, even without surgery. Examples include radiation enteritis.

Diseases Affecting Intestinal Function: While less common causes, certain diseases can damage the intestinal lining and impair absorption, even without surgery. Examples include radiation enteritis.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis typically involves:

![]() Medical History and Physical Exam: The doctor will ask about symptoms, past surgeries, and medical history.

Medical History and Physical Exam: The doctor will ask about symptoms, past surgeries, and medical history.

![]() Blood Tests: To check for nutrient deficiencies, electrolyte imbalances, and liver function.

Blood Tests: To check for nutrient deficiencies, electrolyte imbalances, and liver function.

![]() Stool Tests: To analyze fat content (a sign of malabsorption) and rule out infections.

Stool Tests: To analyze fat content (a sign of malabsorption) and rule out infections.

![]() Imaging Studies: Such as X-rays, CT scans, or MRI, to assess the length and condition of the small intestine.

Imaging Studies: Such as X-rays, CT scans, or MRI, to assess the length and condition of the small intestine.

![]() Endoscopy/Colonoscopy: To visualize the inside of the small intestine and colon, if needed.

Endoscopy/Colonoscopy: To visualize the inside of the small intestine and colon, if needed.

Treatment:

Treatment for SBS aims to:

![]() Maximize Nutrient Absorption:

Maximize Nutrient Absorption:![]()

![]() Dietary Modifications: Frequent, small meals; avoiding simple sugars; limiting caffeine and alcohol; and following specific dietary recommendations from a registered dietitian. The specific diet depends on which part of the small intestine is missing.

Dietary Modifications: Frequent, small meals; avoiding simple sugars; limiting caffeine and alcohol; and following specific dietary recommendations from a registered dietitian. The specific diet depends on which part of the small intestine is missing.![]()

![]() Medications:

Medications:![]()

![]() Anti-diarrheal Medications: To reduce the frequency of bowel movements.

Anti-diarrheal Medications: To reduce the frequency of bowel movements.![]()

![]() Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): To reduce stomach acid, which can worsen diarrhea.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): To reduce stomach acid, which can worsen diarrhea.![]()

![]() H2 Blockers: Another type of acid-reducing medication.

H2 Blockers: Another type of acid-reducing medication.![]()

![]() Growth Hormone (e.g., teduglutide): Can help the remaining intestine adapt and improve absorption.

Growth Hormone (e.g., teduglutide): Can help the remaining intestine adapt and improve absorption.![]()

![]() GLP-2 Analogues: Another type of medication that promotes intestinal growth and function.

GLP-2 Analogues: Another type of medication that promotes intestinal growth and function.![]()

![]() Enzyme Replacement: To aid in digestion.

Enzyme Replacement: To aid in digestion.

![]() Provide Adequate Nutrition:

Provide Adequate Nutrition:![]()

![]() Parenteral Nutrition (PN): Delivering nutrients directly into the bloodstream through a central venous catheter (IV). This is often a life-saving measure for people who can't absorb enough nutrients through their diet. However, long-term PN can have complications, such as liver damage, infections, and blood clots.

Parenteral Nutrition (PN): Delivering nutrients directly into the bloodstream through a central venous catheter (IV). This is often a life-saving measure for people who can't absorb enough nutrients through their diet. However, long-term PN can have complications, such as liver damage, infections, and blood clots.![]()

![]() Enteral Nutrition (EN): Providing liquid nutrition directly into the stomach or small intestine through a feeding tube. This is preferred over PN when possible, as it helps maintain intestinal function.

Enteral Nutrition (EN): Providing liquid nutrition directly into the stomach or small intestine through a feeding tube. This is preferred over PN when possible, as it helps maintain intestinal function.

![]() Manage Complications: Addressing dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, vitamin deficiencies, and other health problems.

Manage Complications: Addressing dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, vitamin deficiencies, and other health problems.

![]() Intestinal Transplantation: In severe cases, when other treatments are not effective, intestinal transplantation may be considered.

Intestinal Transplantation: In severe cases, when other treatments are not effective, intestinal transplantation may be considered.

Adaptation:

The remaining small intestine has the remarkable ability to adapt over time. This process is called intestinal adaptation and involves the intestine increasing its surface area to improve absorption. Factors that promote adaptation include:

![]() Enteral Nutrition: Feeding the intestine encourages it to grow and adapt.

Enteral Nutrition: Feeding the intestine encourages it to grow and adapt.

![]() Growth Factors: Medications like teduglutide stimulate intestinal growth.

Growth Factors: Medications like teduglutide stimulate intestinal growth.

Prognosis:

The prognosis for people with SBS varies depending on the amount of remaining intestine, the underlying cause, and the individual's overall health. Some people can adapt well and eventually reduce or eliminate their need for parenteral nutrition. Others require long-term support. With proper management and care, many people with SBS can lead relatively normal lives.

In summary, short bowel syndrome is a complex condition that requires a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, involving physicians, dietitians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. The goal is to optimize nutrient absorption, provide adequate nutrition, and manage complications to improve the patient's quality of life.