Hemochromatosis (Iron overload)

Published: 18 Jun 2025

ICD9: 275.03 ICD10: E83.118 ICD11: 5C64.1Y

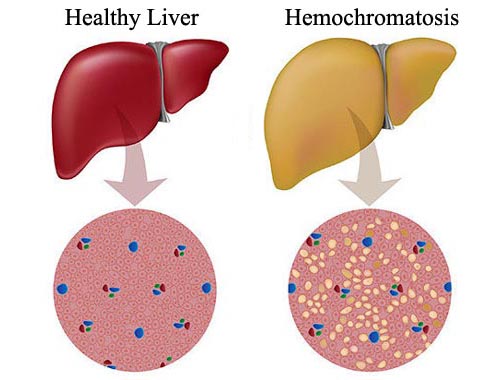

Hemochromatosis, often called iron overload, is a condition where the body absorbs and stores too much iron.

This excess iron can accumulate in various organs, including the liver, heart, pancreas, joints, and skin, leading to significant damage and dysfunction.

Here's a breakdown:

![]() What happens: Normally, your body regulates how much iron it absorbs from food. In hemochromatosis, this regulatory mechanism is faulty, and you absorb more iron than you need. Over time, this excess iron builds up in the body.

What happens: Normally, your body regulates how much iron it absorbs from food. In hemochromatosis, this regulatory mechanism is faulty, and you absorb more iron than you need. Over time, this excess iron builds up in the body.

![]() Types:

Types:![]()

![]() Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HH): This is the most common type and is a genetic disorder, usually caused by mutations in the HFE gene. You inherit the faulty gene from one or both parents.

Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HH): This is the most common type and is a genetic disorder, usually caused by mutations in the HFE gene. You inherit the faulty gene from one or both parents.![]()

![]() Secondary Hemochromatosis: This is caused by other conditions, such as frequent blood transfusions, chronic liver disease, or certain blood disorders that lead to increased iron absorption or administration.

Secondary Hemochromatosis: This is caused by other conditions, such as frequent blood transfusions, chronic liver disease, or certain blood disorders that lead to increased iron absorption or administration.

![]() Symptoms: Symptoms can vary widely and may not appear until middle age (typically after age 40 for men and after menopause for women, due to menstrual iron loss). Early symptoms are often vague and non-specific, which can make diagnosis challenging. Common symptoms include:

Symptoms: Symptoms can vary widely and may not appear until middle age (typically after age 40 for men and after menopause for women, due to menstrual iron loss). Early symptoms are often vague and non-specific, which can make diagnosis challenging. Common symptoms include:![]()

![]() Fatigue

Fatigue![]()

![]() Joint pain (especially in the knuckles of the index and middle fingers)

Joint pain (especially in the knuckles of the index and middle fingers)![]()

![]() Abdominal pain

Abdominal pain![]()

![]() Weakness

Weakness![]()

![]() Bronze or gray skin discoloration

Bronze or gray skin discoloration![]()

![]() Loss of libido

Loss of libido![]()

![]() Erectile dysfunction (in men)

Erectile dysfunction (in men)![]()

![]() Irregular menstrual cycles (in women)

Irregular menstrual cycles (in women)

If left untreated, hemochromatosis can lead to more severe complications, including:![]()

![]() Liver disease: Cirrhosis (scarring of the liver), liver cancer

Liver disease: Cirrhosis (scarring of the liver), liver cancer![]()

![]() Heart problems: Heart failure, arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats)

Heart problems: Heart failure, arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats)![]()

![]() Diabetes: Damage to the pancreas can impair insulin production.

Diabetes: Damage to the pancreas can impair insulin production.![]()

![]() Arthritis: Joint damage

Arthritis: Joint damage![]()

![]() Hypogonadism: Reduced hormone production, affecting sexual function and other bodily functions.

Hypogonadism: Reduced hormone production, affecting sexual function and other bodily functions.![]()

![]() Increased risk of certain infections: Iron can promote the growth of some bacteria.

Increased risk of certain infections: Iron can promote the growth of some bacteria.

![]() Causes:

Causes:![]()

![]() Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HH): Primarily caused by mutations in the *HFE* gene. Other genes, such as *HAMP*, *HJV*, *TFR2*, and *SLC40A1*, can also be involved, but are less common. These genes play roles in iron regulation. A person needs to inherit two copies of the mutated gene (one from each parent) to develop HH, although not everyone with the genes will develop symptoms. Those with one copy are carriers.

Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HH): Primarily caused by mutations in the *HFE* gene. Other genes, such as *HAMP*, *HJV*, *TFR2*, and *SLC40A1*, can also be involved, but are less common. These genes play roles in iron regulation. A person needs to inherit two copies of the mutated gene (one from each parent) to develop HH, although not everyone with the genes will develop symptoms. Those with one copy are carriers.![]()

![]() Secondary Hemochromatosis:

Secondary Hemochromatosis:![]()

![]() Frequent blood transfusions (e.g., for treating thalassemia or sickle cell anemia).

Frequent blood transfusions (e.g., for treating thalassemia or sickle cell anemia).![]()

![]() Chronic liver disease (e.g., hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease).

Chronic liver disease (e.g., hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease).![]()

![]() Certain rare blood disorders (e.g., sideroblastic anemia).

Certain rare blood disorders (e.g., sideroblastic anemia).![]()

![]() Excessive iron intake through supplements or injections.

Excessive iron intake through supplements or injections.

![]() Diagnosis:

Diagnosis:![]()

![]() Blood tests:

Blood tests:![]()

![]() Serum iron: Measures the amount of iron in the blood.

Serum iron: Measures the amount of iron in the blood.![]()

![]() Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC): Measures the blood's capacity to bind iron.

Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC): Measures the blood's capacity to bind iron.![]()

![]() Transferrin saturation: A calculation based on serum iron and TIBC; it reflects the percentage of transferrin (a protein that carries iron in the blood) that is saturated with iron. A high transferrin saturation is a key indicator.

Transferrin saturation: A calculation based on serum iron and TIBC; it reflects the percentage of transferrin (a protein that carries iron in the blood) that is saturated with iron. A high transferrin saturation is a key indicator.![]()

![]() Serum ferritin: Measures the amount of iron stored in the body. Elevated ferritin levels often indicate iron overload.

Serum ferritin: Measures the amount of iron stored in the body. Elevated ferritin levels often indicate iron overload.![]()

![]() Genetic testing: To look for mutations in the *HFE* gene and other related genes.

Genetic testing: To look for mutations in the *HFE* gene and other related genes.![]()

![]() Liver biopsy: In some cases, a liver biopsy may be performed to assess the extent of liver damage and iron accumulation.

Liver biopsy: In some cases, a liver biopsy may be performed to assess the extent of liver damage and iron accumulation.![]()

![]() MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging can be used to assess iron levels in the liver and other organs non-invasively.

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging can be used to assess iron levels in the liver and other organs non-invasively.

![]() Treatment: The primary goal of treatment is to reduce the amount of iron in the body and prevent further organ damage.

Treatment: The primary goal of treatment is to reduce the amount of iron in the body and prevent further organ damage.![]()

![]() Phlebotomy (blood removal): This is the most common treatment. Regular blood removal helps to deplete iron stores. The frequency of phlebotomy depends on the severity of iron overload.

Phlebotomy (blood removal): This is the most common treatment. Regular blood removal helps to deplete iron stores. The frequency of phlebotomy depends on the severity of iron overload.![]()

![]() Chelation therapy: Medications (chelating agents) can bind to iron in the blood and tissues, allowing it to be excreted in the urine or stool. Chelation therapy is typically used when phlebotomy is not feasible (e.g., in cases of severe anemia).

Chelation therapy: Medications (chelating agents) can bind to iron in the blood and tissues, allowing it to be excreted in the urine or stool. Chelation therapy is typically used when phlebotomy is not feasible (e.g., in cases of severe anemia).![]()

![]() Dietary changes: Limiting iron intake from foods (e.g., red meat, iron-fortified foods) and avoiding vitamin C supplements (which enhance iron absorption) can be helpful as adjunctive measures, but diet alone is usually insufficient to manage hemochromatosis. Also avoid alcohol, as it can worsen liver damage.

Dietary changes: Limiting iron intake from foods (e.g., red meat, iron-fortified foods) and avoiding vitamin C supplements (which enhance iron absorption) can be helpful as adjunctive measures, but diet alone is usually insufficient to manage hemochromatosis. Also avoid alcohol, as it can worsen liver damage.

![]() Prognosis: With early diagnosis and treatment, most people with hemochromatosis can live normal lifespans. However, if left untreated, the complications of iron overload can be severe and life-threatening. Liver damage, heart failure, and diabetes can significantly impact quality of life and survival.

Prognosis: With early diagnosis and treatment, most people with hemochromatosis can live normal lifespans. However, if left untreated, the complications of iron overload can be severe and life-threatening. Liver damage, heart failure, and diabetes can significantly impact quality of life and survival.

Important Considerations:

![]() Family history: If you have a family history of hemochromatosis, it's important to get tested, even if you don't have symptoms. Early detection allows for early treatment and can prevent significant organ damage.

Family history: If you have a family history of hemochromatosis, it's important to get tested, even if you don't have symptoms. Early detection allows for early treatment and can prevent significant organ damage.

![]() Genetic counseling: If you are diagnosed with hereditary hemochromatosis, genetic counseling can help you understand the risk of passing the gene to your children.

Genetic counseling: If you are diagnosed with hereditary hemochromatosis, genetic counseling can help you understand the risk of passing the gene to your children.

![]() Monitoring: People with hemochromatosis need regular monitoring to ensure that iron levels are well-controlled and to screen for complications.

Monitoring: People with hemochromatosis need regular monitoring to ensure that iron levels are well-controlled and to screen for complications.

In summary, hemochromatosis is a serious condition that can lead to significant health problems if left untreated. Early diagnosis and management are crucial for preventing organ damage and improving long-term outcomes. If you have any concerns about hemochromatosis, consult with your doctor for evaluation and appropriate management.