Polyarteritis nodosa

Published: 18 Jun 2025

ICD9: 446.0 ICD10: M30.0 ICD11: 4A44.4

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a rare, serious blood vessel disease.

It's a form of systemic necrotizing vasculitis, which means it causes inflammation and damage to the walls of medium-sized arteries throughout the body. This inflammation can lead to:

![]() Narrowing of the arteries: The inflamed artery walls can thicken and narrow, restricting blood flow.

Narrowing of the arteries: The inflamed artery walls can thicken and narrow, restricting blood flow.

![]() Weakening of the arteries: The inflammation can weaken the artery walls, leading to aneurysms (bulges) or even rupture.

Weakening of the arteries: The inflammation can weaken the artery walls, leading to aneurysms (bulges) or even rupture.

![]() Blood clots: Damaged arteries are more prone to forming blood clots, which can further block blood flow.

Blood clots: Damaged arteries are more prone to forming blood clots, which can further block blood flow.

![]() Tissue damage: Reduced blood flow to organs and tissues can cause damage and dysfunction.

Tissue damage: Reduced blood flow to organs and tissues can cause damage and dysfunction.

Key Features & Understanding:

![]() Systemic: PAN can affect almost any organ in the body, including the skin, kidneys, nerves, muscles, and gastrointestinal tract. This means the symptoms can be diverse and vary greatly from person to person.

Systemic: PAN can affect almost any organ in the body, including the skin, kidneys, nerves, muscles, and gastrointestinal tract. This means the symptoms can be diverse and vary greatly from person to person.

![]() Necrotizing: This refers to the death of tissue that occurs due to the inflammation and lack of blood flow.

Necrotizing: This refers to the death of tissue that occurs due to the inflammation and lack of blood flow.

![]() Medium-sized arteries: This is a crucial distinction. PAN primarily affects medium-sized arteries, whereas other vasculitis conditions target different sizes of blood vessels.

Medium-sized arteries: This is a crucial distinction. PAN primarily affects medium-sized arteries, whereas other vasculitis conditions target different sizes of blood vessels.

![]() Not usually associated with ANCA antibodies: Unlike some other forms of vasculitis (like granulomatosis with polyangiitis or microscopic polyangiitis), PAN is typically ANCA-negative. However, there are exceptions.

Not usually associated with ANCA antibodies: Unlike some other forms of vasculitis (like granulomatosis with polyangiitis or microscopic polyangiitis), PAN is typically ANCA-negative. However, there are exceptions.

Causes:

The exact cause of PAN is often unknown (idiopathic). However, certain factors are associated with the condition:

![]() Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) infection: A significant percentage of PAN cases, particularly in the past, were linked to HBV infection. Vaccination against HBV has reduced this association in many parts of the world.

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) infection: A significant percentage of PAN cases, particularly in the past, were linked to HBV infection. Vaccination against HBV has reduced this association in many parts of the world.

![]() Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection: Less common, but still a possible association.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection: Less common, but still a possible association.

![]() Rarely other infections: In very rare instances, other infections might play a role.

Rarely other infections: In very rare instances, other infections might play a role.

![]() Autoimmune disorders: In some cases, PAN might be linked to underlying autoimmune conditions, although the direct link is not always clear.

Autoimmune disorders: In some cases, PAN might be linked to underlying autoimmune conditions, although the direct link is not always clear.

![]() Genetic factors: While not a direct genetic inheritance, certain genes may make individuals more susceptible.

Genetic factors: While not a direct genetic inheritance, certain genes may make individuals more susceptible.

Symptoms:

Because PAN can affect so many different organs, the symptoms are highly variable. Some common symptoms include:

![]() Fever: Often low-grade and persistent.

Fever: Often low-grade and persistent.

![]() Fatigue: Extreme tiredness and weakness.

Fatigue: Extreme tiredness and weakness.

![]() Weight loss: Unintentional weight loss.

Weight loss: Unintentional weight loss.

![]() Muscle aches (myalgia): Pain in the muscles.

Muscle aches (myalgia): Pain in the muscles.

![]() Joint pain (arthralgia): Pain in the joints.

Joint pain (arthralgia): Pain in the joints.

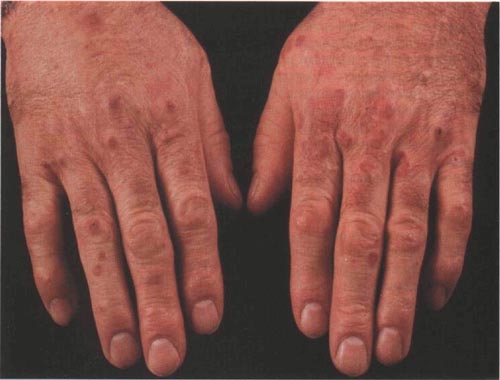

![]() Skin manifestations:

Skin manifestations:![]()

![]() Livedo reticularis: A lacy, net-like rash on the skin.

Livedo reticularis: A lacy, net-like rash on the skin.![]()

![]() Subcutaneous nodules: Painful lumps under the skin, often along the course of affected arteries.

Subcutaneous nodules: Painful lumps under the skin, often along the course of affected arteries.![]()

![]() Skin ulcers: Sores that don't heal easily.

Skin ulcers: Sores that don't heal easily.

![]() Nerve damage (neuropathy): This can cause numbness, tingling, pain, or weakness, particularly in the hands and feet (mononeuritis multiplex).

Nerve damage (neuropathy): This can cause numbness, tingling, pain, or weakness, particularly in the hands and feet (mononeuritis multiplex).

![]() Kidney problems: High blood pressure, protein in the urine, and kidney failure.

Kidney problems: High blood pressure, protein in the urine, and kidney failure.

![]() Abdominal pain: Pain in the abdomen, often after eating.

Abdominal pain: Pain in the abdomen, often after eating.

![]() Gastrointestinal bleeding: Bleeding from the digestive tract.

Gastrointestinal bleeding: Bleeding from the digestive tract.

![]() High blood pressure: Hypertension.

High blood pressure: Hypertension.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosing PAN can be challenging due to the variable symptoms. The process typically involves:

![]() Medical history and physical examination: The doctor will ask about your symptoms, medical history, and conduct a physical exam.

Medical history and physical examination: The doctor will ask about your symptoms, medical history, and conduct a physical exam.

![]() Blood tests:

Blood tests:![]()

![]() Inflammatory markers: ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and CRP (C-reactive protein) are often elevated, indicating inflammation.

Inflammatory markers: ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and CRP (C-reactive protein) are often elevated, indicating inflammation.![]()

![]() Complete blood count (CBC): May show elevated white blood cell count.

Complete blood count (CBC): May show elevated white blood cell count.![]()

![]() Kidney function tests: To assess kidney involvement.

Kidney function tests: To assess kidney involvement.![]()

![]() Liver function tests: To assess liver involvement

Liver function tests: To assess liver involvement![]()

![]() Hepatitis B and C testing: To check for viral infections.

Hepatitis B and C testing: To check for viral infections.![]()

![]() ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies): Typically negative in classic PAN, but may be done to rule out other forms of vasculitis.

ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies): Typically negative in classic PAN, but may be done to rule out other forms of vasculitis.

![]() Urine analysis: To check for protein or blood in the urine.

Urine analysis: To check for protein or blood in the urine.

![]() Angiography: An X-ray of the blood vessels after injecting a contrast dye. This can help identify aneurysms, narrowing, or blockages in the affected arteries.

Angiography: An X-ray of the blood vessels after injecting a contrast dye. This can help identify aneurysms, narrowing, or blockages in the affected arteries.

![]() Biopsy: A small tissue sample from an affected area (e.g., skin, nerve, muscle) is examined under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis. This is often considered the gold standard.

Biopsy: A small tissue sample from an affected area (e.g., skin, nerve, muscle) is examined under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis. This is often considered the gold standard.

![]() Imaging studies: CT scans, MRI, or ultrasound may be used to assess organ involvement.

Imaging studies: CT scans, MRI, or ultrasound may be used to assess organ involvement.

Treatment:

Treatment for PAN aims to suppress the inflammation and prevent further damage to the blood vessels and organs. The main treatments include:

![]() Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone): Powerful anti-inflammatory drugs used to reduce inflammation quickly.

Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone): Powerful anti-inflammatory drugs used to reduce inflammation quickly.

![]() Immunosuppressants (e.g., cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate): These drugs suppress the immune system to prevent it from attacking the blood vessels. Cyclophosphamide is often used for more severe cases, while azathioprine or methotrexate may be used for maintenance therapy.

Immunosuppressants (e.g., cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate): These drugs suppress the immune system to prevent it from attacking the blood vessels. Cyclophosphamide is often used for more severe cases, while azathioprine or methotrexate may be used for maintenance therapy.

![]() Antiviral medications: If the PAN is associated with hepatitis B, antiviral drugs will be used to treat the viral infection.

Antiviral medications: If the PAN is associated with hepatitis B, antiviral drugs will be used to treat the viral infection.

![]() Other medications: Depending on the affected organs, other medications may be needed to manage specific symptoms, such as high blood pressure, pain, or kidney problems.

Other medications: Depending on the affected organs, other medications may be needed to manage specific symptoms, such as high blood pressure, pain, or kidney problems.

Prognosis:

The prognosis for PAN depends on the severity of the disease, the organs involved, and how quickly treatment is started. Without treatment, PAN can be fatal. However, with early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, many people with PAN can achieve remission and live relatively normal lives.

Important Note: This information is for general knowledge and does not constitute medical advice. If you suspect you have PAN, it is crucial to see a doctor for diagnosis and treatment. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical for improving outcomes. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making any decisions related to your health or treatment.