Ulcer (Peptic Ulcer, Stomach Ulcer)

Published: 18 Jun 2025

ICD9: 533.90 ICD10: K27.9 ICD11: DA61

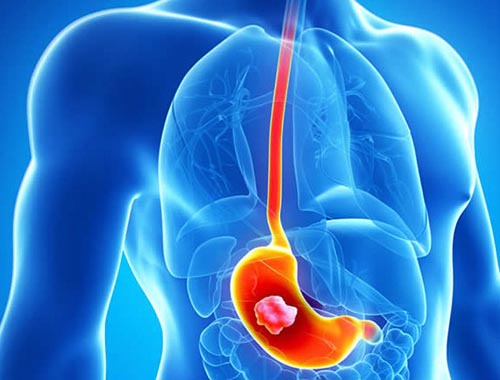

An ulcer, specifically a peptic ulcer, is a sore that develops on the lining of the stomach, esophagus, or small intestine.

When referring to an ulcer, most people typically mean a peptic ulcer, and even more specifically, a stomach ulcer.

Here's a breakdown:

![]() Location: Peptic ulcers can occur in the:

Location: Peptic ulcers can occur in the:![]()

![]() Stomach (Gastric ulcer): Most commonly referred to as a stomach ulcer.

Stomach (Gastric ulcer): Most commonly referred to as a stomach ulcer.![]()

![]() Esophagus (Esophageal ulcer): Less common.

Esophagus (Esophageal ulcer): Less common.![]()

![]() Duodenum (Duodenal ulcer): The first part of the small intestine, these are more common than stomach ulcers.

Duodenum (Duodenal ulcer): The first part of the small intestine, these are more common than stomach ulcers.

![]() Cause: Previously, stress and spicy foods were thought to be the primary causes. Now, it's understood that the most common causes are:

Cause: Previously, stress and spicy foods were thought to be the primary causes. Now, it's understood that the most common causes are:![]()

![]() _Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)_ infection: A type of bacteria that can infect the stomach lining, leading to inflammation and ulcers.

_Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)_ infection: A type of bacteria that can infect the stomach lining, leading to inflammation and ulcers.![]()

![]() Long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Medications like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve) can damage the stomach lining. Aspirin, even low-dose aspirin, can also increase ulcer risk.

Long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Medications like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve) can damage the stomach lining. Aspirin, even low-dose aspirin, can also increase ulcer risk.

![]() Symptoms: The most common symptom is a burning stomach pain. However, symptoms can vary depending on the location and severity of the ulcer. Other symptoms include:

Symptoms: The most common symptom is a burning stomach pain. However, symptoms can vary depending on the location and severity of the ulcer. Other symptoms include:![]()

![]() Burning stomach pain: Often described as gnawing or aching, it can be worse between meals or at night. Eating may temporarily relieve the pain from a duodenal ulcer, but can worsen the pain from a gastric ulcer.

Burning stomach pain: Often described as gnawing or aching, it can be worse between meals or at night. Eating may temporarily relieve the pain from a duodenal ulcer, but can worsen the pain from a gastric ulcer.![]()

![]() Bloating

Bloating![]()

![]() Heartburn

Heartburn![]()

![]() Nausea or vomiting

Nausea or vomiting![]()

![]() Feeling full easily

Feeling full easily![]()

![]() Loss of appetite

Loss of appetite![]()

![]() Weight loss

Weight loss![]()

![]() Dark or black stools (due to bleeding)

Dark or black stools (due to bleeding)![]()

![]() Vomiting blood (may look like coffee grounds)

Vomiting blood (may look like coffee grounds)

![]() Complications: If left untreated, ulcers can lead to serious complications:

Complications: If left untreated, ulcers can lead to serious complications:![]()

![]() Bleeding: Ulcers can bleed, leading to anemia or more severe blood loss. This can be slow and chronic, or sudden and severe.

Bleeding: Ulcers can bleed, leading to anemia or more severe blood loss. This can be slow and chronic, or sudden and severe.![]()

![]() Perforation: The ulcer can eat a hole through the stomach or intestinal wall, leading to a life-threatening infection (peritonitis).

Perforation: The ulcer can eat a hole through the stomach or intestinal wall, leading to a life-threatening infection (peritonitis).![]()

![]() Obstruction: Swelling and scarring from an ulcer can block the passage of food through the digestive tract.

Obstruction: Swelling and scarring from an ulcer can block the passage of food through the digestive tract.![]()

![]() Gastric cancer: Chronic H. pylori infection is a major risk factor for gastric cancer.

Gastric cancer: Chronic H. pylori infection is a major risk factor for gastric cancer.

![]() Diagnosis: Doctors use various tests to diagnose ulcers:

Diagnosis: Doctors use various tests to diagnose ulcers:![]()

![]() Upper endoscopy: A thin, flexible tube with a camera is inserted down the esophagus to view the stomach and duodenum. Biopsies can be taken to test for _H. pylori_ or other problems.

Upper endoscopy: A thin, flexible tube with a camera is inserted down the esophagus to view the stomach and duodenum. Biopsies can be taken to test for _H. pylori_ or other problems.![]()

![]() Upper GI series (Barium swallow): The patient drinks a barium solution, which coats the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. X-rays are then taken to visualize the organs. This is less common now due to the better visualization offered by endoscopy.

Upper GI series (Barium swallow): The patient drinks a barium solution, which coats the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. X-rays are then taken to visualize the organs. This is less common now due to the better visualization offered by endoscopy.![]()

![]() _H. pylori_ tests:

_H. pylori_ tests:![]()

![]() Breath test: The patient drinks a special liquid, and the breath is analyzed to detect _H. pylori_.

Breath test: The patient drinks a special liquid, and the breath is analyzed to detect _H. pylori_.![]()

![]() Stool test: A stool sample is tested for _H. pylori_.

Stool test: A stool sample is tested for _H. pylori_.![]()

![]() Blood test: A blood sample can detect antibodies to _H. pylori_, but it can't distinguish between an active infection and a past infection.

Blood test: A blood sample can detect antibodies to _H. pylori_, but it can't distinguish between an active infection and a past infection.![]()

![]() Biopsy: A tissue sample taken during endoscopy is tested for _H. pylori_.

Biopsy: A tissue sample taken during endoscopy is tested for _H. pylori_.

![]() Treatment: Treatment focuses on reducing stomach acid, protecting the lining of the stomach and intestines, and, if present, eradicating _H. pylori_.

Treatment: Treatment focuses on reducing stomach acid, protecting the lining of the stomach and intestines, and, if present, eradicating _H. pylori_.![]()

![]() Medications:

Medications:![]()

![]() Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): Reduce stomach acid production (e.g., omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole).

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): Reduce stomach acid production (e.g., omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole).![]()

![]() H2-receptor antagonists: Also reduce stomach acid production, but are generally less potent than PPIs (e.g., ranitidine, famotidine). (Ranitidine has been recalled in many countries, so check with your doctor or pharmacist).

H2-receptor antagonists: Also reduce stomach acid production, but are generally less potent than PPIs (e.g., ranitidine, famotidine). (Ranitidine has been recalled in many countries, so check with your doctor or pharmacist).![]()

![]() Antibiotics: Used to eradicate _H. pylori_. Typically a combination of two or three antibiotics is used, along with a PPI.

Antibiotics: Used to eradicate _H. pylori_. Typically a combination of two or three antibiotics is used, along with a PPI.![]()

![]() Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol): Can help protect the stomach lining and also has some antibacterial activity against _H. pylori_.

Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol): Can help protect the stomach lining and also has some antibacterial activity against _H. pylori_.![]()

![]() Antacids: Neutralize stomach acid and provide temporary relief (e.g., calcium carbonate, aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide).

Antacids: Neutralize stomach acid and provide temporary relief (e.g., calcium carbonate, aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide).![]()

![]() Cytoprotective agents: Help protect the lining of the stomach and duodenum (e.g., sucralfate, misoprostol).

Cytoprotective agents: Help protect the lining of the stomach and duodenum (e.g., sucralfate, misoprostol).![]()

![]() Lifestyle changes:

Lifestyle changes:![]()

![]() Avoid NSAIDs: If possible, avoid NSAIDs or use them at the lowest effective dose. Talk to your doctor about alternative pain relievers.

Avoid NSAIDs: If possible, avoid NSAIDs or use them at the lowest effective dose. Talk to your doctor about alternative pain relievers.![]()

![]() Avoid smoking: Smoking delays healing and increases the risk of recurrence.

Avoid smoking: Smoking delays healing and increases the risk of recurrence.![]()

![]() Limit alcohol: Alcohol can irritate the stomach lining.

Limit alcohol: Alcohol can irritate the stomach lining.![]()

![]() Diet: While bland diets are no longer considered crucial, avoiding foods that trigger your symptoms can be helpful. Common triggers include spicy foods, acidic foods (like citrus fruits), and caffeinated beverages. Eating smaller, more frequent meals can sometimes help.

Diet: While bland diets are no longer considered crucial, avoiding foods that trigger your symptoms can be helpful. Common triggers include spicy foods, acidic foods (like citrus fruits), and caffeinated beverages. Eating smaller, more frequent meals can sometimes help.![]()

![]() Surgery: Surgery is rarely needed but may be necessary in cases of complications like perforation, obstruction, or severe bleeding that cannot be controlled with medication.

Surgery: Surgery is rarely needed but may be necessary in cases of complications like perforation, obstruction, or severe bleeding that cannot be controlled with medication.

Important Considerations:

![]() See a doctor: If you suspect you have an ulcer, it's essential to see a doctor for diagnosis and treatment. Self-treating can be dangerous and can delay proper care.

See a doctor: If you suspect you have an ulcer, it's essential to see a doctor for diagnosis and treatment. Self-treating can be dangerous and can delay proper care.

![]() Complete the full course of treatment: If you are prescribed antibiotics for _H. pylori_, it is crucial to complete the entire course, even if you start feeling better. Incomplete treatment can lead to antibiotic resistance.

Complete the full course of treatment: If you are prescribed antibiotics for _H. pylori_, it is crucial to complete the entire course, even if you start feeling better. Incomplete treatment can lead to antibiotic resistance.

![]() Follow-up: Your doctor may recommend a follow-up endoscopy to ensure that the ulcer has healed, especially if you have a gastric ulcer.

Follow-up: Your doctor may recommend a follow-up endoscopy to ensure that the ulcer has healed, especially if you have a gastric ulcer.

In summary, a peptic ulcer is a sore on the lining of the stomach, esophagus, or duodenum, most commonly caused by _H. pylori_ infection or long-term NSAID use. Symptoms include burning stomach pain, and complications can be serious if left untreated. Diagnosis involves endoscopy and tests for _H. pylori_, and treatment includes medications to reduce acid, protect the lining, and eradicate the bacteria if present. Prompt medical attention is essential.